Figure 1: Tardigrade illustration (with thanks to!) © David Krenz

If you walk down a busy city street, surrounded by cars, buses, and the urban smog of traffic, it might be hard to imagine that another world exists just a few centimetres away. Yet within the mosses and lichens covering the bark of street trees, tardigrades or “water bears” live in their own microcosm. These almost invisible creatures are revealing how urban pollution shapes living communities, offering key insights into the hidden impacts of city life on biodiversity.

A video of tardigrades from the work of the author (Dr. Alfonsina A. Grabosky)

Resilient, but not invincible

Tardigrades are renowned for their resilience, they can withstand boiling temperatures, freezing conditions, radiation, and even the vacuum of space. However, their survival still depends on key environmental factors: the amount of moss or lichen on a tree, its moisture, or the surface’s acidity. In cities, added pressures such as vehicular traffic determine which species persist or vanish, directly linking human activity to biodiversity at microscopic scales.

Why cities and vehicular traffic?

By 2050, more than two-thirds of the global population is expected to live in cities. This rapid urban expansion leads to increased traffic and vehicle emissions, resulting in higher pollution levels, more buildings, and reduced green spaces. Among the most harmful pollutants from traffic are fine particles known as PM2.5, which carry serious health risks. Yet, urbanisation does not only affects people, but it also acts as a major force transforming global biodiversity, including at the smallest scales.

A case from northern Argentina

To explore this question, researchers examined tardigrade communities in a rapidly growing city in northern Argentina, situated in a mountainous region and experiencing a significant increase in vehicular traffic over the past decade. Samples were collected from mosses and lichens on street trees located along roads with high, medium, and low traffic intensity. The study was repeated in both summer and winter to assess whether seasonality altered the outcomes. Over 2,200 tardigrades representing 11 species were identified, offering an unusually detailed perspective on how these organisms respond to urban pressures.

What the research revealed

Seasonal changes made little difference to how many tardigrades were found or how many species lived there. Whether in the hot, humid summer or the cold, dry winter, their communities stayed much the same. This stability likely comes from their ability to enter cryptobiosis: a kind of deep sleep that lets them survive until conditions improve.

Traffic-related pollution strongly influenced tardigrade communities. Species richness —the number of different species in a place — was low in areas with high vehicular traffic, where only a few species dominated. In contrast, low-traffic areas supported a wider variety of species living more evenly. Medium-traffic areas were the most unstable, probably because fluctuating pollution levels created unpredictable conditions that made it harder for sensitive species, like tardigrades, to survive.

Two tardigrade species stood out as ecological indicators: organisms that reveal how healthy or polluted an environment is. Macrobiotus olgae was able to live even in areas with high vehicular traffic and high levels of PM2.5, showing a strong tolerance to pollution. Milnesium quiranae, on the other hand, almost disappeared from those polluted sites, suggesting it is more sensitive. Together, these species show how tardigrades can help scientists detect both resilience and vulnerability in urban ecosystems.

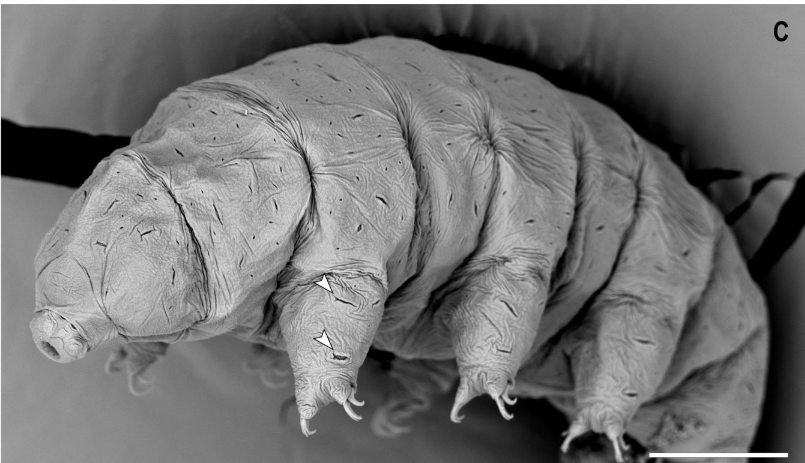

Figure 1: A tardigrade (Macrobiotus olgae) seen under scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The arrowheads point to the lenticular pores on its surface. Scale bar = 10 μm. (From Rocha et al., 2024).

Why it matters

If vehicle emissions are making tardigrade communities simpler —with only a few hardy species managing to survive — other small, less visible organisms are probably being affected in the same way. When a rich mix of species is replaced by just a few that can tolerate pollution, different places begin to look more alike, and many distinctive local species may quietly disappear, leaving urban ecosystems poorer and less resilient.

Tardigrades also offer clear advantages as bioindicators: organisms that help reveal the health of an environment. They are widespread, inexpensive to study, and closely linked to conditions in their tiny habitats. Using them provides a practical, low-cost way to complement conventional air quality and biodiversity assessments, which is especially valuable in developing regions where resources for environmental monitoring are limited.

Tiny giants with a big message

These microscopic animals remind us that the story of urban pollution is written in the smallest forms of life. Their resilience is extraordinary, yet it has limits: even tardigrades, famed for their toughness, can be shaped by particulate matter and the hidden pressures of city life. Their presence—or absence—offers early warnings of ecosystem health, making them valuable indicators for citizen science projects that empower communities to monitor environmental change locally.

Next time one walks along a tree-lined street, it is worth imagining the unseen worlds thriving on the bark just above eye level. Among them, tardigrades continue to ask an urgent question: what kind of cities are being built, and for whom—not only for people, but also for the countless small organisms that share these spaces?

Original article

Grabosky A, González-Reyes A, Méndez M, et al. Influence of traffic-related pollution and seasonality on tardigrade diversity in urban ecosystems Insect Conservation and Diversity 2025; 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/icad.12838

References

González-Reyes A, Rocha A, Corronca, et al. Effect of urbanization on the communities of tardigrades in Argentina. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 2020; 188: 900–912. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz147

Ostertag B, Rocha M, González-Reyes A, et al. Effect of environmental and microhabitat variables on tardigrade communities in a medium-sized city in central Argentina. Urban Ecosystems 2022; 26(2): 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-022-01303-x

Rocha A, Camarda D, Doma I, et al. Macrobiotus olgae sp.: a new urban, limno-terrestrial eutardigrade (Tardigrada, Macrobiotidae) from Argentina. Organisms Diversity and Evolution 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13127-024-00663-w

Roszkowska M, Gołdyn B, Wojciechowska D, et al. How long can tardigrades survive in the anhydrobiotic state? A search for tardigrade anhydrobiosis patterns. PLoS One 2023; 18: e0270386. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270386

Leave a comment